Last time on the blog we discussed inorganic natural pigments: natural colors from mineral, geological sources. This time we will talk about natural organic (meaning, containing tetrahedral carbon, as opposed to inorganic carbonates or graphite or diamond) pigments, of plant and animal origin.

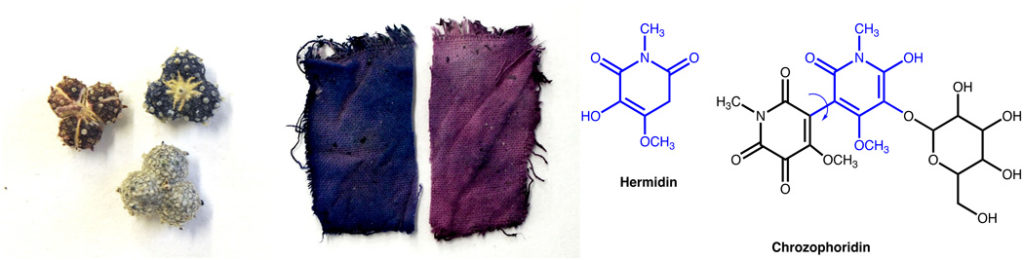

But first, some breaking news: An organic pigment, thought to be lost to history, has been rediscovered in its plant source, and has been for the first time chemically characterized. Portuguese scientist Paula Nabais, from the Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and her colleagues reported last week in Science Advances (a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science) the results of a thorough historical and chemical investigation into folium, a stable blue pigment used in the Middle Ages for manuscript illumination, but unfamiliar and unavailable to artists in the modern era. Dr. Nabais and her colleagues read primary sources from the Middle Ages up to the 19th century CE to learn how medieval artists identified the plant (Chrozophora tinctoria) and extracted its water-soluble blue color (including some tricks and tips that may have stymied modern researchers trying to recreate the historical pigment). They then used state-of-the-art spectroscopic techniques and computer modeling to elucidate the exact chemical structure of the pigment extracted from the plants and to confirm its absorption spectrum. The pigment thus described was new to science, and was given the name chrozophoridin by Dr. Nabais and her coauthors. This is very exciting, and may lead to this ancient color returning to modern works of art.

Organic (and organometallic) pigments differ from the inorganic pigments because of the presence of organic carbon. Carbon has several chemical forms: carbonate, graphite, diamond, and organic. Organic carbon’s particular chemical properties and reactivity have made it the basis for all biochemicals (at least on this planet). Carbon becomes organic by way of photosynthesis, in which carbon dioxide (a non-ionic inorganic form of carbon) is reduced (meaning, electrons are added), and incorporated into (at first) simple sugars, which then go on in metabolism to make carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, nucleic acids – all the useful biochemicals. Most biochemicals are, however, largely colorless, particularly in solution; think of egg whites (proteins) or sugar syrup (carbohydrates). They absorb ultraviolet light, but we can’t see this (sometimes, if the absorption spectrum is strong enough, these look somewhat yellow, as the absorption peak spills over into visible light). However, some biochemicals, including some that are in coordination with metal ions, have chemical structures that result in absorption peaks in the visible wavelength range, which means they have color. These compounds, or the portions of the compounds that are responsible for light absorption (if it’s a large compound) are frequently called chromophores.

The alternating single and double bonds give rise to its familiar orange color.

What gives chromophores their optical properties is a particular chemical structure: alternating single and double bonds (often called conjugated bonds) between carbon atoms. This structure creates a ‘cloud’ of electrons with energy levels that can be similar to visible light photons (and thus result in absorption of the photon). The location and shape of the resulting absorption peaks depends on the number of conjugated bonds, and the shape of the structure itself. Orange and yellow carotenes, for example, are long lines of conjugated bonds, with some stuff at either end. Rings are frequently found in these structures. In The Science of Pigments we talked about the porphyrin rings that bind up metal ions to make chlorophyll or heme (found in hemoglobin or cytochromes). Open up this ring, remove the metal ion, and you get a bilin, which is a chromophore found in blue-green algae or, yes, bile. Eww.

An important chemical structure that is often part of chromophores is a ring of six carbon atoms, with alternating single and double bonds that make what is called an aromatic structure. Aromatic structures are very important biochemicals because they not only occur in strong-smelling compounds (thus the name), but they are also very chemically and physically stable. They resist chemical and physical attack quite well. Hold that thought, because one of the main factors that regulate whether a biological pigment is useful for making artistic pigment is its stability. We don’t use chlorophyll a as a painting pigment in part because if you expose it to acidic conditions or even just look at it funny the chromophore will give up its magnesium ion and turn from a lush blue-green color to a dispiriting gray in an instant. And the brilliant colors of anthocyanins of flowers (and purple carrots) can fade quickly (how disappointing it is to cook a purple carrot and see that color lost – in this case the orange or yellow carotenes are far more stable than the purple anthocyanins).

But for a moment let’s consider the role of pigments in organisms. In some cases, but not necessarily all, the color of the pigment plays some sort of crucial role in the life of the organism; sometimes the color is incidental. But, the electronic arrangements that make them able to absorb light makes them uniquely useful as biochemicals. Pigments, such as chlorophylls, absorb light energy for the purpose of photosynthesis; also, pigments can block excess light from damaging cells, like the yellow lutein or flavonoids found in land plants, or melanin in some mammals. Pigments, such as cytochromes (heme containing) are involved in electron transport chains in everything from bacteria on up, used in photosynthesis and respiration to generate chemical energy for cells. Lots of vitamins contain chromophores – and in fact the important role of translating light flux into nerve impules in the eye is played by a carotenoid derivative, retinol. Red colored heme is also found in hemoglobin, where it is used to transport oxygen through blood in many organisms. And, importantly, organisms use pigments as color for recognition purposes (colors and patterns so members of the same species can recognize each other so as to avoid mating … accidents, warning coloration for poisonous organisms), and for stealth. The bright colors of flowers, often from a diverse group of organic compounds called anthocyanins, help their pollinators recognize them (many bees can see into the ultraviolet so some flower pigments have features invisible to our eyes but stand out quite obviously to the right bee). Unfortunately, despite the wide range of colors all across the spectrum that can be produced by organic pigments, not all are suitable for making paints or dyes. The main reason for this is stability. Many of these biochemicals are evolved to be reactive: biochemical processes in the cells transform them into something else, but they can subsequently be recycled by other biochemical processes. Away from the cellular machinery that maintains them, organic pigments can break down, fall into disrepute, become fugitive.

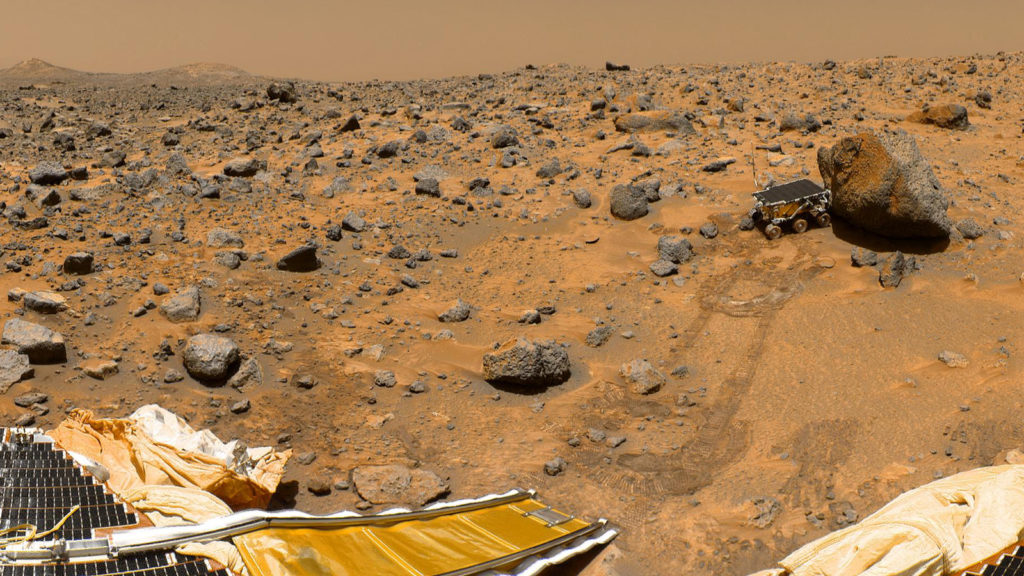

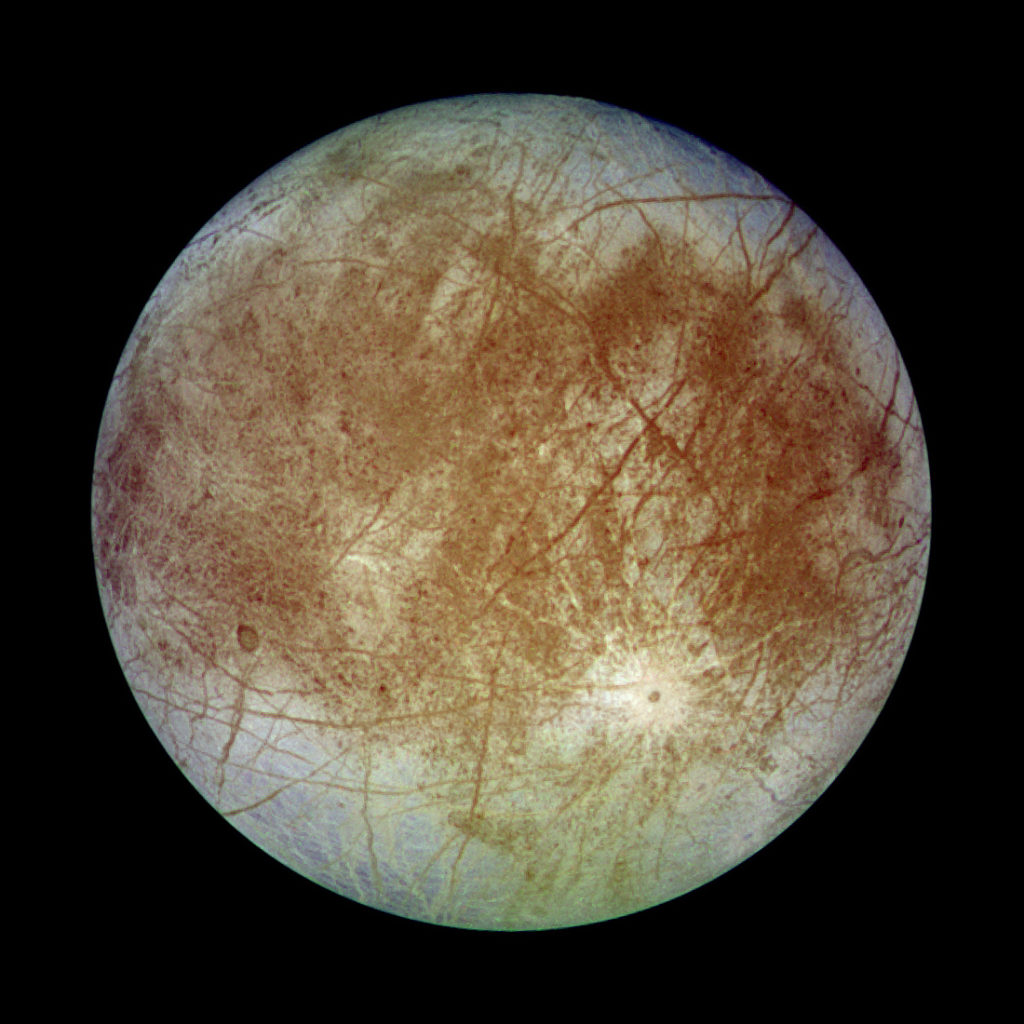

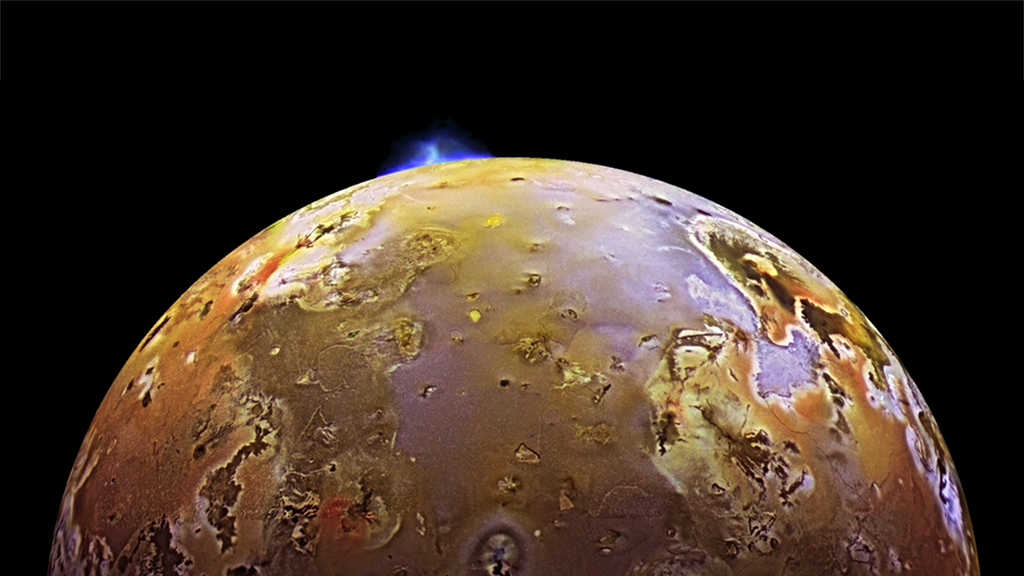

This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

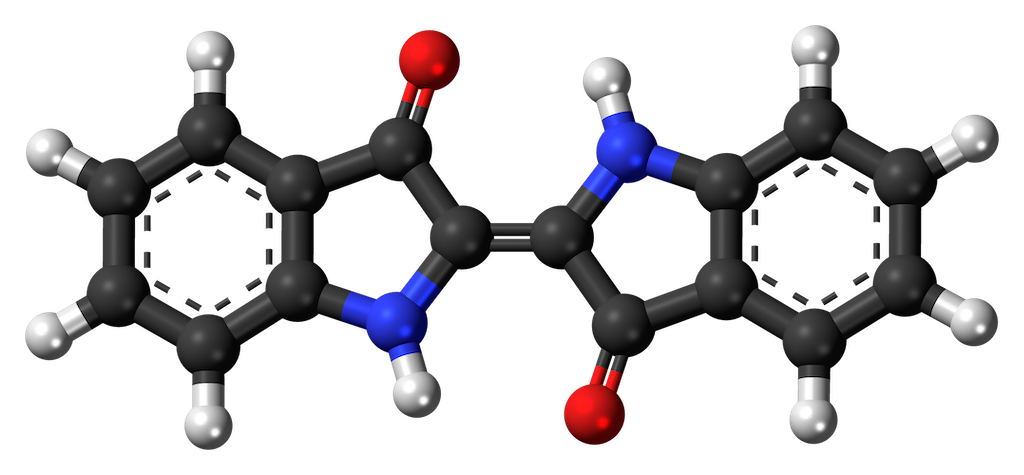

One example of a reputable, upright, good citizen amongst organic pigments is the familiar blue of indigo. Indigo has a chemical structure that contains not one but two of those aromatic rings, in part leading to its resistance to degradation by enzymes and ultraviolet radiation. The exact role of indigo and its precursors in the cell is obscure, but it is derived from the amino acid tryptophan (which does not make you sleepy, and isn’t particularly abundant in turkey, but contains an aromatic ring, and is a component of most proteins and enzymes in all cells). Indigo is also widely distributed, occurring in multiple plant species around the world. The same pigment is found in ‘true indigo’ in the Indian subcontinent, woad in Europe, anil in America, and dyer’s knotweed in Asia. Amazingly enough the important historical color Tyrian purple contains essentially the same chemical compound as does indigo and woad, but its source is the shell of a marine snail.

Indigo requires some chemical gymnastics to properly implement as a dye or pigment (the topic of a future article?) but once extracted and properly prepared, provides a stable and beautiful color.

Another important historical color that is known to be less of a good pigment citizen is madder. Madder is a medium sized (up to 4′) plant whose roots contain a couple different closely related anthoquinones (not terribly different from the quinine in your gin and tonic, cheers), alizarin and purpurin. These can function as antioxidants and antimicrobials in the plant, and incidentally happen to have crimson and purple colors that were much prized in the middle ages for dyeing. Madder is known to be rather fugitive as a pigment for paints (mean it breaks down over time as a result of oxidation by oxygen or sunlight), and has been largely replaced by synthetic dyes. However, madder gives us a good transition to the end of this article, as madder is one of the earliest examples of pigments that were known to have been chemically altered by people to make their properties more useful. Next time we’ll talk about ancient and modern methods of altering natural products to better suit our purposes.

Thank you for joining us as we do Pandemic Projects, meant to keep you energized, curious and learning!